The Continental Divide Raceway was a wheelie big deal

Picture of Continental Divide Raceway financier, Sid Langsam, courtesy of the Sandi nee Langsam Reichborn-Kjennerud collection.

In the late 1950s, Douglas County’s Continental Divide Raceway (CDR) was drawing the top names in automobile racing, but tragedy, lawsuits and health issues ultimately closed the track.

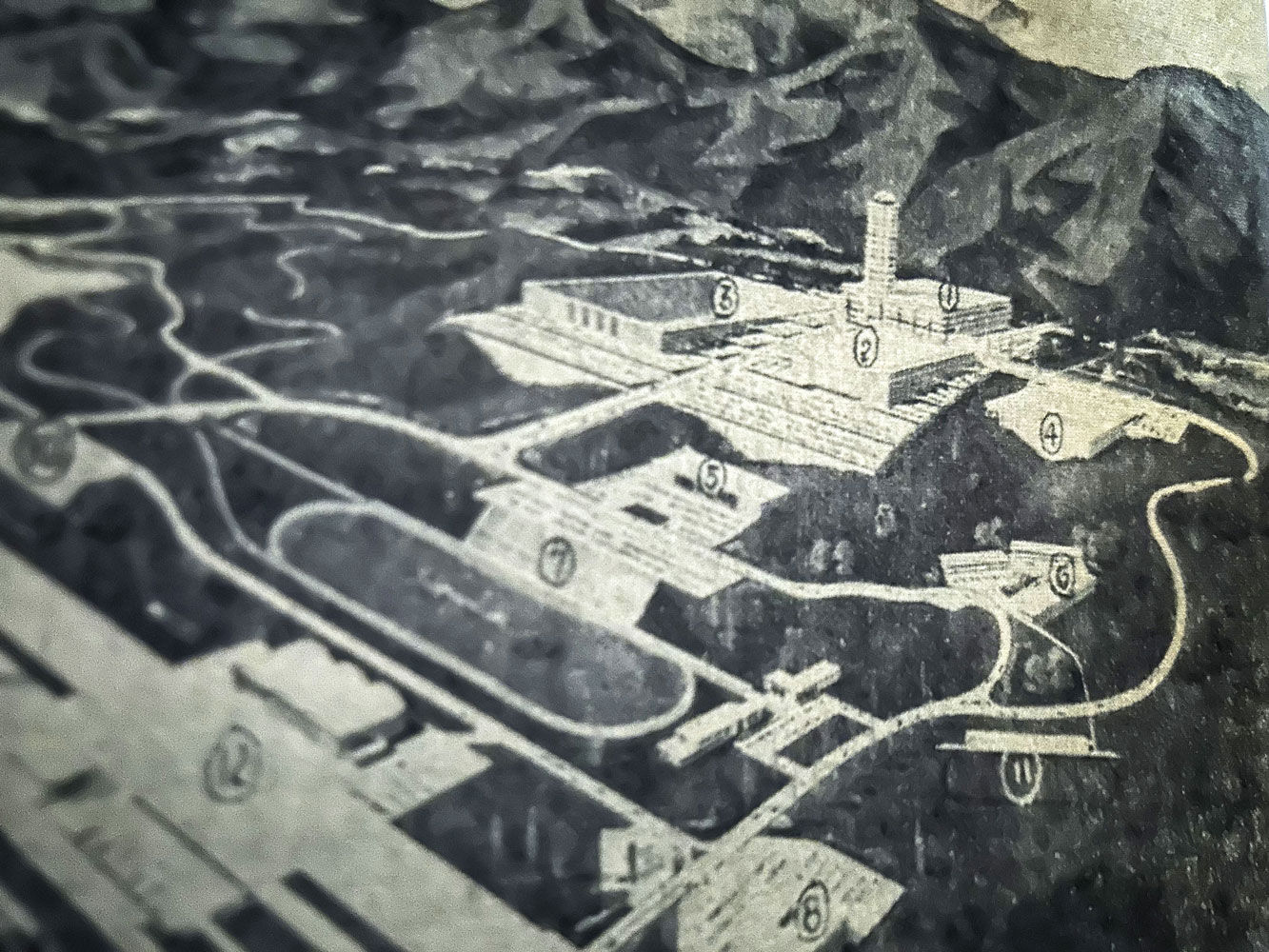

The facility was merely three miles south and west of Castle Rock. Capable of accommodating any type of motor racing, CDR was, at build out, planned to seat 75,000 fans and another 30,000 in a field house.

As with all big ideas, the plan for CDR required money. The concept began with the purchase of 1,520 acres of land from James and Bea Lowell, a parcel once a chunk of the current CALF Ranch east of I-25. Boldly advertised in the December 1956 Douglas County News, CDR’s groundbreaking was scheduled for May 5, 1957. As with most massive projects, things did not go swimmingly. The targeted capital could not be raised and, but for a Lubbock, Texas financier named Sid Langsam who was fascinated with the concept, CDR would have been stillborn.

On July 19, 1959, CDR opened its doors, and the first noteworthy race was on August 8 where 94 cars participated, consisting mainly of locals with big horsepower. The following day, a 22.4-mile affair sanctioned by the Sports Car Club of America was attended by 4,000 fans and drew 8,000 bystanders. Bob Donner, driving a Porsche RSK, took the gold medal. On the same weekend, Patsy Randle of Wyoming won the women’s race driving an Alpha Romeo Super Spider.

Sid had a flair for promotion. As CDR’s reputation expanded, he attracted marquee names in the sport as well as its funny cars and the often wackier people who drove them. Among the celebrities who showed were A.J. Foyt, Bobby Unser, Don Garlits, Mario Andretti, Tommy Ivo and Evel Knievel. By 1966, Alan Bockla became a member of the 200 Club when his top speed exceeded 200 mph.

By 1960, CDR hosted the motorcycle Grand Prix of Colorado and the race had increased in length to 50 miles.

Drag racing was also a big draw, though such events were generally not held concomitant with race track affairs. For the layman, drag racing entails two super-charged cars that race each other with massive, slick wheels. Often, they did wheelies (where the front wheels lift off the pavement) to see who could reach the top speed in a quarter of a mile. One could race in a stock car (an unaltered vehicle), a modified car. or even a funny car, souped up in ways known only to the mechanic.

CDR’s racing season ran from April through October, and the challenges of weather could be legion. Though the track was widened and made safer in many areas, one could never know what disasters might occur.

Though 1968 was the track’s finest year for the road course, higher speeds brought on serious collisions and then a fatal accident. Despite record attendances, and more demanding, dramatic races and racers, a $2 million negligence lawsuit was filed against Sid and others in 1973. Affected also by his diagnosis of cancer and lacking a buyer, Sid pulled the plug on CDR.

To learn more about CDR and its history, look for James Hansmann’s book Racing with Altitude. James grew up among these ideas and big wheels and is today a curator at the downtown Castle Rock Historical Society and Museum. His book is available there or on Amazon.

Architectural sketch of the $33 million sports center to-be, taken from the Douglas County News, December 27, 1956.

By Joe Gschwendtner; photos courtesy of James Hansmann’s book, Racing with Altitude